Things I Learned Setting Up WiFi from Scratch on Linux

Anthony OleinikRoughly half a year ago, I decided to get into home labbing. I’ve aged a decade since then.

I’ve learned:

- Talos Linux has decided to not support WiFi: I do not blame them.

- there’s a certain subset of the internet patching the government out of their Linux kernels.

- WiFi is complex, hard, and only for experts and the unreasonably stubborn.

- hostapd is a great way to host a wireless access point - it does seem to be the only option, after all.

- Any Linux machine can be a WiFi endpoint. That being said, I would never attempt this on any distro besides NixOS because at least on NixOS you can see your battle scars declaratively.

This isn’t going to be a tutorial, rather an infotainment-esque story, with lots of learning along the way.

I: How We Got Here

It started off simple - I just wanted to run an instance of tldraw. Google did as Google does and depreciated Jamboard - as a visual explainer and fellow human, I tend to communicate in diagrams, and tldraw is a fantastic medium for said diagrams.

Long story short, I managed to successfully host an app publicly using Cloudflare tunnels and external DNS. Major props to the Kubernetes community: every path was extremely well lit, regardless of how hard I chose to make things for myself.

After that, I wanted to run some apps local to my network only - things like the Longhorn UI, or grafana - these should not be exposed to the internet - or the “WAN”, I say in a look-at-me-and-what-I’ve-learned manner. My router was not very user-friendly - I decided to go the 5G home internet route, which was seamless except for all the seams: TMobile home internet comes with OpenWRT with no user configurabilty - so I couldn’t run a custom DNS server.That being said - to all my non-technical friends, I absolutely recommend TMobile home internet - its stupid easy to setup for non-power users. For shame!

I was not deterred, though: every problem had a solution if you looked far enough - and far enough I had to look.

II: Local DNS, Attempt One: Not local at all

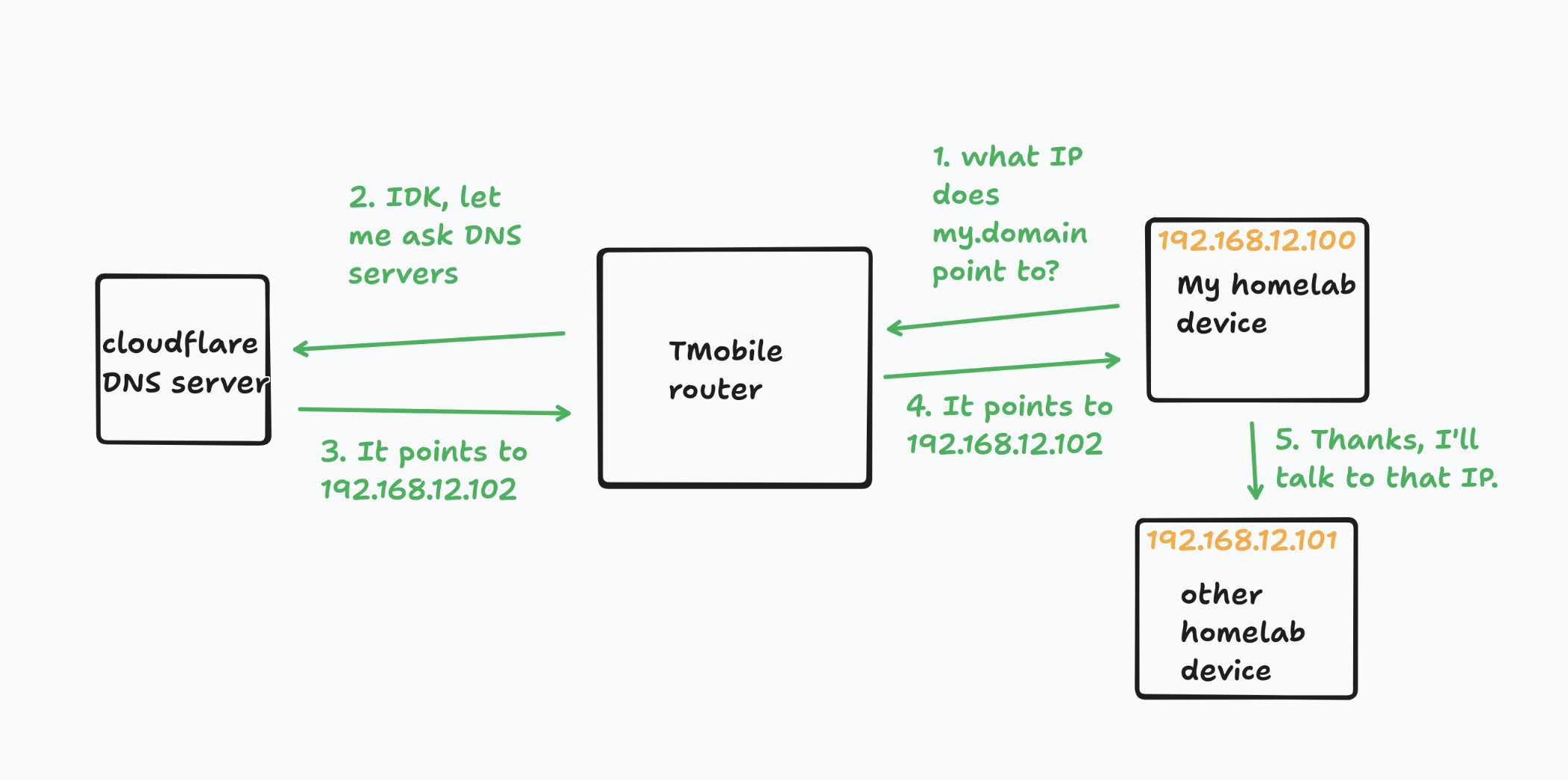

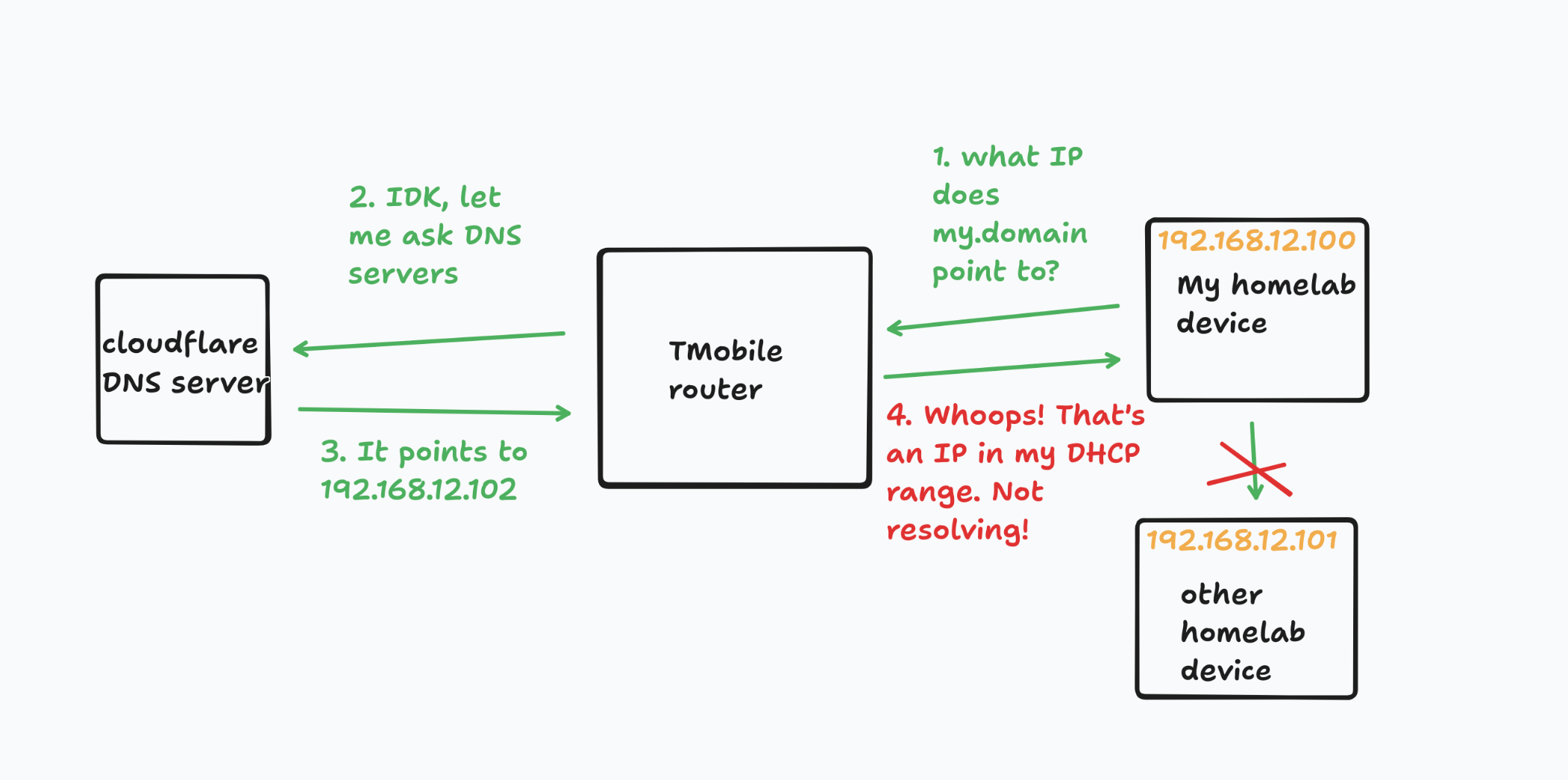

I wrote a blog post about an absurd idea that actually “worked”: more or less, we’d mint DNS records that point to local DHCP IPs. For anyone else in the world, this is pretty useless: for people connected to my home internet, you’d be routed to the device!

This worked, except for one small caveat: OpenWRT runs DNS rebind protection by default - which means OpenWRT will scrape any DNS records that point to local IPs and just pretend they don’t exist.

Helpfully, OpenWRT provides an option to toggle this off: unhelpfully, TMobile does not expose this option. Onward!

III: Local DNS: Welcome to the Jungle

Lets begin this section assuming you are me, before I was able to cobble something together that worked.

There are a lot of protocols between your WiFi password and your connection to the internet: it’s a miracle it works at all, reallyI suppose this is economics driven: people do seem to be willing to pay to not have to carry around a Cat6 cable..

This section will be visualized in NixOS configuration snippets, which I also use to justify the perhaps-conceivably grandiose title: I did this all in NixOS, which means I may now look back at my work and find exactly what is misconfigured. If I were to buy the exact same device, I could very easily put the same WiFi configuration on a new box over there: I won’t, because I would never buy the same device again, but I could should I want tothat being said, now that I hold the knowledge in my head I would be able to adapt it as necessary..

That being said, knowing nix is absolutely not required to understand the rest of this article: if you do not know nix, treat it as fancy json. If you do know nix, probably still treat it as fancy json.

III.I: Northstar, Where We’re Headed

In so many words, we’re going to “dual NAT” our way out of this bag. Nat stands for “Network Area Translation”: in short, the world is critically running out of IPv4 addresses. If we gave one to every smart TV, we’d be totally outVery smart people came up with IPv6, and some would say that you could skip NAT and all this complex stuff with IPv6, although it seems the internet suffers from colossal IPv4 inertia.. The solution is to reserve specific blocks of IPv4 range into local-only network addresses. If you’ve ever seen the address 127.0.0.1, colloquially named “local host”, you’re familiar with reserved IP ranges. Any IP starting with 192.168.x.x is reserved for local addresses: These are LAN addresses, or addresses on the local network only.

A fun and fancy tool we can use to see these things is arp-scan: arp-scan allows us to send ARP pingsugh! more acronyms. Address resolution protocol, which should hopefully soon be self explanatory. to devices on our network:

$ sudo arp-scan -l

Interface: enp42s0, type: EN10MB, MAC: 00:00:00:00:00:00, IPv4: 192.168.12.158 # look, its us! our local ip!

Starting arp-scan 1.10.0 with 256 hosts (https://github.com/royhills/arp-scan)

192.168.12.1 00:00:00:00:00:00 (Unknown)

192.168.12.98 00:00:00:00:00:00 LCFC(HeFei) Electronics Technology co., ltd

192.168.12.123 00:00:00:00:00:00 Intel Corporate

192.168.12.147 00:00:00:00:00:00 LG Innotek # my tv. It's currently "off". not off enough to not respond to an arp ping, i guess.You’ll see MAC addresses, which are little id’s written on the hardware itself, along with the assigned DHCP address, on the left hand sideas a side note: I learned this too late for it to be useful, but -d flag will replace the IP with an assigned DNS name by the router - most of the time, it will be hostname.local..

We’ll have the router that TMobile gave us talk to exactly one device: our router. So, for our TMobile router, the LAN side is exactly one device. For our router, the LAN side is exactly all the devices on our network, including my iPhone and Smart TV. What is the counterpart to the LAN side? The WAN side, of course! The WAN, or “Wide Area Network”, is the side of the router that basically means “My IP proxies all the IP’s on my LAN side”. On the WAN side of our Linux router sits a single device, the TMobile home internet box. On the WAN side of the TMobile box sits the rest of the world!

We can’t speak DNS through the TMobile box, though: we must be sneaky. Instead, we’ll host our own DNS server internally, and TMobile will never know about it. That way, we can write whatever records we damn please, and TMobile has no say in the matter.

III.II: Hardware

I’ve lived my whole life as a software developer - the kind of software where “provision a machine” means increment the count field in a terraform resource. I must admit, though: hardware is where true wizardry happens.

We’re looking at a m90n-1 lenovo Mini-PC. Helpfully, it’s equipped with two ways to connect to some network: a WiFi card, of the Intel flavor, and a good-old-Ethernet port.

We’ll need them both.

You see, to talk to many things at once, we need multiple network interfaces. We’ll connect the ethernet cord to the TMobile box, then, and use the WiFi card as the access point for the rest of the devices. It won’t be fast, because our tiny router will now have to shove everything through a single ethernet port, but it will be fast enough for the types of devices I’m going to connect to the network. They shouldn’t really want to query the world much anyway - moreso talk to each other.

III.III: The Final Protocol: DHCP

One final protocol we must talk about, though. Assigning IP’s to a local network is not as easy as forward iterating through a list of IP’s: if a device connects to our endpoint, and asks for an IP, we could look in our IP range and assign out 192.168.12.1. We now know to take any packet that comes from that device and rewrite it as if it came from us, and then blast it out to the world. When we get our response, re-rewrite it and put their assigned IP right back on it. Voila, we’ve performed area translation!

But what if that device never comes back? We would soon run out of IPs in our own block. We could LRU IPs, but we’re now in complicated territory: the protocol that manages these IPs is DHCP. It likely solves a whole host of other problems I have not thought of. Since I myself have never ran into those problems, I guess it solves them well.

III.IV: Lets write some code

This next part will be much less fun, since it’s just configuring stuff. If you’re not using this as a tutorial and instead as infotainment, I’d advice you skip down to the next section.

SSHing to our soon-to-be router, lets figure out the names of the network interfaces:

[manager@whiterun:~]$ ifconfig

enp2s0: flags=4163<UP,BROADCAST,RUNNING,MULTICAST> mtu 1500

inet 192.168.12.98 netmask 255.255.255.0 broadcast 192.168.12.255

...

lo: flags=73<UP,LOOPBACK,RUNNING> mtu 65536

inet 127.0.0.1 netmask 255.0.0.0

...

wlo1: flags=4099<DOWN,BROADCAST,MULTICAST> mtu 1500

inet 192.168.10.1 netmask 255.255.255.0 broadcast 192.168.10.255

...You’ll see that enp2s0 has a LAN address. You’ll also see it on wlo1, but enp2s0 has is not the one this device is communicating on, since it did not show up in arp-scan and it is down. This, then, is the ethernet address. lo is localhost or loopback, which you can tell since its address is 127.0.0.1. Then wlo1 is the WiFi interface. So, we want enp2s0 to be the WAN side, or the side that talks to the router. wlo1 is the LAN side, or the side that talks to our devices.

Lets assign these to variables:

let

wan-if = "enp2s0";

lan-if = "wlo1";

in {

# TODO: write everything

}Here’s some nix that configures those interfaces:

systemd.network = {

networks = {

"10-${wan-if}" = {

matchConfig.Name = wan-if;

linkConfig.RequiredForOnline = "carrier";

networkConfig = {

# tell this interface that it speaks IPv4 DHCP; that is, we can get

# an address.

DHCP = "ipv4";

};

};

# LAN side

"30-${wan-if}" = {

matchConfig.Name = lan-if;

linkConfig.RequiredForOnline = "enslaved";

address = [

# since this interface is not given an address via DHCP, we must give

# it one ourselves!

"192.168.10.1/24"

];

networkConfig = {

ConfigureWithoutCarrier = true;

};

};

};

};

I should note that this is pretty stripped down. I left a lot of detail out because I’m not trying to be a direct tutorial.

We need to have the LAN side be able to speak to the WAN side. For this, we setup nftables rules:

chain forward {

type filter hook forward priority filter; policy drop;

iifname { "${lan-if}" } oifname { "${wan-if}" } accept comment "Allow trusted LAN to WAN"

iifname { "${wan-if}" } oifname { "${lan-if}" } ct state { established, related } accept comment "Allow established back to LANs"

}Again, stripped down, but the critical parts are here.

III.V: Wi-Fi, or Back to Banter

Now that we’re done with the boring part, lets go back to the wild west.

Do you remember my hook for this article? the quip about some Linux users patching the government out of their kernel? We’re finally here.

Wi-Fi, for most people, is strictly magic. For me, it is basically strictly magic, but ever so slightly less magic.

Wi-Fi runs on Radio waves. This means that wireless signals can interfere with each other: If you live in an apartment building, you along with all your neighbors Wi-Fi’s are probably attempting to find low interference channels - that is, channels where not a lot of other devices are running on.

Do you know who else uses Wi-Fi, besides civilians? Governments. Police, Firefighters, probably the CIA but in an encrypted capacity. It would suck if their radios did not work because I was running my Wi-Fi on channels that they talk over: instead of hearing critical communications, they’re listening to undecipherable gibberish. Not great!

Sensibly, certain frequencies are allocated for the government to use. When I was configuring my Wi-Fi, I had absolutely no idea that this was the case: likely, when configuring my WiFi channel, I probably almost stomped on a police radio channel. Luckily for me and for the police, hostapd, the most-used WiFi software, takes a country code parameter, which does not let you connect to your countries protected radio channels.

Two notes here:

- this is only for initiating on this channel. Nobody can tell that you’re listening to the channels.

- these are just protections for your sake.

But what if you configure your region incorrectly? I was going to make a joke here about people being too stupid to configure their own devices, but I decided to omit it. I actually think that what I’m about to say is not a bad idea: there are probably a huge amount of people who copied their hostapd config from the internet. There are probably a huge amount of people who did not bother editing the region of whatever config they copied, and as such are running under the wrong region.

To this end, the Linux kernel has enabled lar, location aware regulatory. Essentially, your Linux device will snoop around neighboring WiFi’s and attempt to figure out where in the world it is, and apply the regulations of said region. This move was deeply unpopular - this kernel bug thread is actually pretty funny of a read, I’d highly recommend.

I won’t post them here, but there are kernel patches floating around that disable LAR. We won’t be going that route.

Some say LAR has been poorly written, and often infers the wrong region. Perhaps it does, but mine does not. Despite my LAR inferring US as it is supposed to, it still disables all frequencies, a common symptom of LAR failure.

Going to even deeper corners of the internet, there exists a true hacker written a patch to get hostapd working on intel WiFi chips.Summarizing their discovery, when hostapd takes control of the network card, it does not wait for LAR to step in and provide the region and incorrectly assumes it cannot be set. To be extra safe, it does not let you broadcast on any 5GHz network. The patch amounts to adding a LAR scan call and a 10 second sleep.

services.hostapd = {

enable = true;

package = pkgs.hostapd.overrideDerivation (old: {

version = "2.10";

src = pkgs.fetchurl {

url = "https://w1.fi/releases/hostapd-2.10.tar.gz";

sha256 = "0pcik0a6yin9nib02frjhaglmg44hwik086iwg1751b7kdwpqvi0";

};

patches = lib.singleton (pkgs.fetchpatch {

# https://superuser.com/questions/1645797/using-hostapd-on-ubuntu-20-04-to-create-5ghz-access-point-channel-153-primary

# 5GHz does not work with hostapd without this patch.

url = "https://tildearrow.org/storage/hostapd-2.10-lar.patch";

sha256 = "USiHBZH5QcUJfZSxGoFwUefq3ARc4S/KliwUm8SqvoI=";

});

});Once that patch is in, it’s back to business!

IV: Conclusion

Once again, I don’t want this to become a tutorial. If you’re looking to configure your Linux machine as a WiFi device, I believe this gives you ample starting ground and hammers out the really crazy bits.

Here’s my finished WiFi configuration with everything in there - go crazy using it as a resource if you’d like. If you were just here for the story, I hope I’ve satisfied your curiosity!

My next journey, instead of actually running any services, will be to get PXEBoot going over WiFi using a Linux devicesomething like a Raspberry PI with WiFi enabled. to ethernet bridge via IP forwarding.